July 15, 2015

By Rebecca Hughes

At least once a week, someone mistakes me for a prostitute. It started two years ago when I moved to south Tel-Aviv. At first I didn’t understand why cars were pulling up alongside me as I walked home, trailing me for a few moments and then driving away. After a few months I casually mentioned this strange behavior to one of my neighbors.

“They think you’re a prostitute,” she stated matter-of-factly. I must have looked offended, because she quickly added, “Don’t worry, it’s not just you. It happens to me too.”

Suddenly, many odd interactions began to make sense. For instance, the man who stopped me on street, insisting that he knew me.

“Don’t I know you?” he asked, looking me up and down.

“I don’t think so.” I responded.

“Ahh…” he hesitated.

“Can I help you with something? Do you need directions?”

“Yes, yes. I need directions.”

“Where to?”

“Ahh…never mind,” he mumbled over his shoulder as he walked quickly away.

Men would approach me in the middle of the day when I was on my way to a meeting, or at night when I was coming back from the gym. Sometimes I was able to laugh about it, but mostly I was annoyed and angry. Annoyed that I had to interact with sex-buyers who just assumed that a woman walking alone was a prostitute, and angry that they were permitted to purchase the sexual services they felt entitled to from women who lacked my privilege. Yes, I was annoyed and angry. But I wasn’t frightened until March 19, 2015.

Men would approach me in the middle of the day when I was on my way to a meeting, or at night when I was coming back from the gym. Sometimes I was able to laugh about it, but mostly I was annoyed and angry. Annoyed that I had to interact with sex-buyers who just assumed that a woman walking alone was a prostitute, and angry that they were permitted to purchase the sexual services they felt entitled to from women who lacked my privilege. Yes, I was annoyed and angry. But I wasn’t frightened until March 19, 2015.

It was a perfectly ordinary Thursday morning in south Tel Aviv. People were going to work, or walking to the market, or on their way to the bus stop. On the corner of Har-Zion and Salame, less than 100 meters from my apartment, a 37-year-old woman was walking her dog. Suddenly, a man ran up to her, slammed her against the wall of an apartment building, threw her to her knees, pulled down his pants, and sodomized her.

The attack lasted for ten minutes. For ten minutes, the woman tried to fight him off. For ten minutes, she struggled and screamed as people walked by, glanced at her and then looked away, and continued along their way. For ten minutes, dozens of people who passed her on their way to work and school paid her no notice. Taxis pulled up next to where she was kneeling and then drove off. Buses drove by.

After ten minutes, one person stopped and called the police. As the sirens approached, the attacker pulled up his pants and casually strolled away.

Now let us consider why, in the warm daylight of an ordinary Thursday morning, dozens of people witnessed a vicious sexual assault in progress, but averted their gazes, closed their ears to the victim’s screams, continued texting or talking on their cell phones, and kept walking. Let us consider why no one called out to the woman to ask if she needed help. Why no one shouted at the attacker, even from a distance. Why the rape continued for ten long, horrific minutes, before one person decided to call the police.

I’ve asked a lot of people this question, and it made all of them uncomfortable. Several surmised that it was due to the “bystander effect,” a theory which proposes that when there are many witnesses to an attack, people tend to assume that “someone else” will help, or are afraid to be the first to intervene; and thus watch but don’t act, or walk away.

It’s an interesting theory to ponder. But let’s consider something even more interesting: people witnessing an attack are less likely to intervene if they think the attacker is the victim’s husband or boyfriend. In controlled experiments, researchers found that when the woman yelled, “Get away from me; I don’t know you,” onlookers intervened more often than not. But if the woman instead yelled “Get away from me; I don’t know why I ever married you,” most people just walked by. The assumption is that there are circumstances in which a man has a right to assault a woman.

And, of course, if the passers-by assume the woman is a prostitute…well, then, it’s to be expected. Normal. All in a day’s work. It’s an understandable assumption, because paying for sex is legal in Israel; and researchers have long demonstrated that in areas where prostitution is legal or tolerated, a “culture of prostitution” takes root, strengthening the idea that men’s “needs” entitle them to women’s bodies. It’s no surprise that in areas where prostitution is tolerated, rates of gender-based violence rise. A man may have to pay for the right to sexually assault a woman today, but tomorrow he may just assault her.

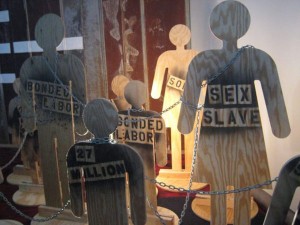

In Israel, the law and the associated culture have helped to create and sustain an enormous industry built on human trafficking. Thousands of women and girls—poor immigrants, runaway teens, women fleeing abusive homes, Jews and Arabs alike—are lured by traffickers. They’re recruited personally by individuals, strangers or friends, or they respond to newspaper ads promising high-paying jobs. When they meet with the prospective “employer,” they’re sold to pimps and brothel owners. Hotels provide special deals to the pimps, who hire drivers to transport the women to and from “clients.” Impoverished and imprisoned in brothels and discreet apartments, the typical victim is forced to submit to being raped by as many as 15 men a day.

For the past three years, I served as a coordinator for the Task Force on Human Trafficking, a joint project of ATZUM – Justice Works and Kabiri-Nevo-Keidar law firm. TFHT works to engage and educate the public and government agencies, lobbies for reform in the areas of prevention, border closure, protection of escaped women, and prosecution of traffickers and pimps. The effort to confront and eradicate modern slavery in Israel has proven to be an uphill battle. Recent allegations that a member of the Knesset has been involved in pimping and drugs only underscore the complexity and deep roots of Israel’s human trafficking industry.

On March 19th a woman was violently attacked in broad daylight, and dozens of witnesses did nothing. Unfortunately, I’m not surprised. Israelis in general, and residents of Tel-Aviv in particular, have determined that the monetized sexual assault of prostituted women is acceptable. But it is not just the women in prostitution who suffer society’s callousness and apathy. All women will pay the price. What happened that Thursday morning in March in my neighborhood happens every day, and in many neighborhoods: people looked at a woman, and saw a commodity.

Rebecca Hughes, an avid blogger whose work has been published in the “Times of Israel” and the “Jerusalem Post”, served as Coordinator for ATZUM’s Task Force on Human Trafficking Project from 2012 – 2015. She is now studying towards a Master of Science in Foreign Service at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., from where she coordinates TFHT’s international online lobbying initiative, Project 119.”